When a publicly traded company earns a profit, it also earns a decision.

There are two routes frequently taken: reinvest the profit back into the business (called retained earnings), or distribute that money to its shareholders. The later is called a dividend, and we can think of this as an outsourcing of that initial decision to the consumer. The power to take the money out or put it back in now lies in their hands.

To investors, dividends are a choice with a dollar tag: to reap the rewards as they stand, or to reinvest them with the hope they compound into the future. And since each decision comes with an associated price, the tradeoffs are easily quantifiable via dollars and cents.

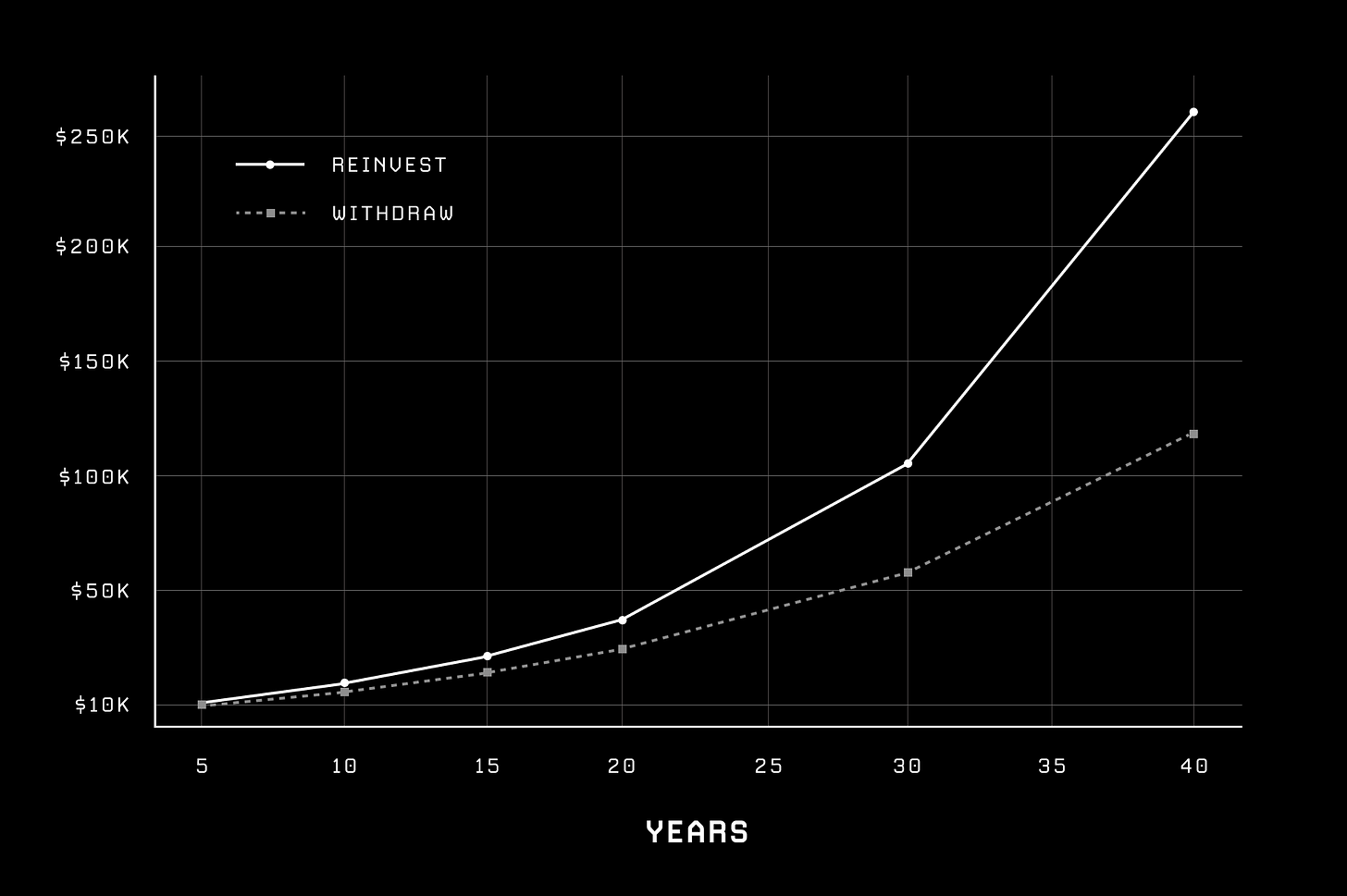

So, let’s add some context with a quick thought experiment. Consider an initial investment in an S&P 500 ETF, and say it comes with relatively standard returns (~6.5% YOY adjusted for inflation) and dividends (~2% payout, quarterly). For a round number, say we start with $10K. Let’s look at what the difference is between re-investing those dividends back into the stock after each pay-out vs. withdrawing the cold, hard cash:

At the tail end, a $150k gulf forms between the two strategies. Not only does reinvestment outperform withdrawal at the end point, but it also outpaces at each step along the way. The gap grows exponentially larger as time - and compounding - work their magic.

Winning strategy, resoundingly clear.

So why don’t we think about acquiring knowledge in the same way?

Intellectual Dividends

Dividends are a powerful analogy when extended to the domain of knowledge acquisition and personal growth.

In finance, we can think of them as a reward paid out to shareholders for their investment. You put dollars behind a company you believe to be of high quality, and - if your bet is correct - the company rewards you for your show of faith with a payout of either cash or stock.

Learning works in a similar fashion, with analogous inputs and outputs. You invest your time and energy (capital) into a source of information (company) and get rewarded with some form of acquired knowledge (dividend).

Financial Dividends, meet Intellectual Dividends.

But how can we acquire the dividends in the first place? Here, it is useful to look through the lens of the financial markets. And when we do, a simple yet instructive truth emerges: bad companies rarely pay out good dividends.

This is because dividends are a sign of underlying business health: you cannot pay out your shareholders with money that you do not have; the capital must come from somewhere. That somewhere is oftentimes called ‘profit’, which tends to be generated by strong underlying business fundamentals. We can thus think of dividends as a positive indicator for a good company, and to obtain them requires you invest in businesses capable of producing them.

Similarly, in the domain of knowledge, intellectual dividends are an indicator for the underlying quality of the content from which they come. The higher the signal of the information, the more you will get paid out in return.

But as in the financial markets, existence is no guarantee for value. There are thousands of companies that investors would be best served avoiding, and content is no different. In the grand scheme of information, there are few sources that possess the fundamentals capable of returning intellectual dividends back to you. Most offer the illusion of returns by promising us signal, yet in the end only give us noise.

So we must do the work to find them, recognizing that intellectual dividends will not magically appear without effort.

And once we do, we earn ourselves a decision: withdraw, or invest?

Tangibility

As in our example from above, the optimal scenario is clear.

Like in finance, the ultimate power of knowledge acquisition lies in playing the long game. The more we acquire - and the more we reinvest - the greater the compounding we will see.

The key to unlocking compounding growth from intellectual dividends lies in application. We must take the knowledge we acquire and put it to work. This is the point of continuous learning - not to acquire knowledge for knowledge’s sake, but rather to apply it in a way such that it solidifies into wisdom.

Yet we don’t often perceive the process of learning in this way; perhaps 10% of what we learn gets applied, if we are lucky. That is because a clear distinction exists between the nature of the returns in the two domains: whereas financial dividends are tangible, intellectual dividends are often the exact opposite: intangible.

Unlike in finance where we can put a clear, objective ‘price tag’ on our returns, the rewards that come from the acquisition of new knowledge are harder to pin down. Learning as a process is highly abstract - it is difficult to know both when the payout comes and what form it takes. Is it once we finish the book or article? After we’ve taken a test or passed a certification? Hard to say.

As a result, we often fail to grasp what we are being paid out as a result of our investment into a resource. And if we don’t know what it is we are taking away, then the process of putting it back in - of reinvesting - becomes exponentially harder.

This is most commonly where we fall short in our processes of learning - not in the initial investment, but in what we do with the returns.

We have our withdrawals set up on auto-pilot, causing us to miss out on the long term compounding effects that arise from application. Rather than reinvesting acquired knowledge, we push it deep into the confines of our mental filing cabinets knowing we are unlikely to ever bring it back into the light. We read, listen, and converse - only to let what we’ve gained slip away.

We are passively investing our attention, hoping that our energy expenditure on the front end is enough to reap the rewards on the backend. But it is not. Unlike their financial parallels, intellectual dividends do not function in a ‘set it and forget it’ type manner. There is no equivalent in the pursuit of knowledge to the up-front, automatic reinvestment strategy you might find in your favorite brokerage app.

Instead, it requires a fundamentally active commitment to reinvesting acquired knowledge for gain. Without an emphasis on application, the gap between what you do have and what you could have grows.

The key to bringing back more from our intellectual pursuits thus lies in recognition that our ROI is directly correlated with our effort.

The more we work to apply the insights we gain, the more tangible our intellectual dividends become.

Application: Making the Intangible Tangible

So, if our ability to maximize the returns on our intellectual pursuits requires moving from intangible to tangible, from consumption to application, then what does this looks like in practice?

Here, optionality is our friend. There are a number of routes we can travel that allow for us to capture the power of the compounding curve. But I find three specific ones to be most powerful - creating, teaching, and connecting.

1. Create

An area where schools have gotten it right, project based learning has long been used as a mechanism through which to solidify knowledge. Why? Because a concrete deliverable serves as a forcing function for making ideas tangible; it gives one the immediate opportunity to apply - to re-invest - the information you acquire (this is in fact the rationale for this Substack).

What this looks like can take many forms - you can tweet lessons, riff longform on ideas, design a visual, build a product, and much more. Each gives you an opportunity to remix and refine your original idea. Each forces you take an abstract thought and bring it to life.

The point is not what you create so much as the fact that you do. That you take a blueprint and turn it into a house. The more we create, the more we build, the more solidified our foundation of understanding becomes.

2. Teach

There is an old maxim: You haven’t taught until they have learned. In the domain of intellectual dividends, the reverse is true as well: you haven’t learned until you have taught.

Teaching is a powerful lever for understanding as it forces you to understand the idea at a fundamental level. When the goal is to be understood rather than heard, refinement becomes paramount. You must strip away the noise, condensing your thought into a densely packaged idea for your audience.

So to start, find someone you can use as a sounding board; someone willing to be the student for your ideas (apologies to my wife for frequently filling this role for me). And for a helpful framework, try borrowing from the Fenyman Technique: Select your content; teach it to a child; refine your understanding; and then pay attention to the results.

Read to acquire. Teach to solidify.

3. Connect

The world does not exist as a combination of siloes. Instead, it is an interconnected web of domains, a puzzle made of overlapping pieces that come together to form the whole.

Knowledge works in the same way. An idea from one domain can - and most likely will - carry weight when applied to another. True wisdom thus does not exist as isolated facts, but instead lies in the connections between them.

And so, a third powerful strategy for applying acquired learnings is to find connections; to take one idea and fuse it with another. Rather than building something new, here we instead look to blend it with that which we already know.

We can think of this strategy as re-investing our dividends into a new company - putting them to work in a slightly different way by attempting to bridge gaps across domains. We do so by looking for transferable concepts, principles from one domain that can easily apply to another. By identifying the similarities that underly two concepts, we can create a bridge between them. We can reason by analogy.

This piece itself serves as an example. It is a connection drawn between two domains, between finance and knowledge. The ‘dividend’ serves as common link between the two, an analogy that bridges our understanding of two seemingly distinct concepts, solidifying our understanding of both in the process.

Connecting concepts thus reinforces the strength of each idea, making each anchor point stronger together than either could be on their own. So to further buttress your ideas, look for the opportunities to build bridges between them.

Which path you choose to follow matters little - there is no ‘best strategy’, only what is best for you. But the point remains: reinvesting your intellectual dividends requires focused action, an intent to take the knowledge you have built and make it tangible through application.

We must take action, start putting one foot in front of the other. Applying one thing at a time. Yet taking the steps is not always easy - even once we know exactly where we must go. Sometimes, like a prize horse in a derby, we need a spur to jolt us forward.

Rules

Practical frameworks give us an excellent starting point but are no guarantee we will cross the finish line. What we do in between is what determines the outcome of the race.

Oftentimes, there is a barrier that exists to creating forward momentum; an activation energy that must be overcome. That barrier arises as a function of choice - the more we give ourselves, the easier it is for us to find a way out. To skip the follow through and move on to something else.

So in order to ensure our intellectual dividends are reinvested, we must account for our natural human tendency to eschew the current thing for the new one; to fall short of application out of a desire to find what is next. To do so, we can tap into the power of constraints.

Constraints - or rules - create structure. And all good endeavors need them. Their presence clearly defines the boundaries within which we operate, and thus the game we play.

Constraint begets action. A shot clock spurs a shot. A play clock spurs a snap. A pitch clock spurs a pitch. The more confined our options become, the more the path towards action crystalizes.

In the same way, we can implement rules that force us to action when combined with our frameworks. Here are two of my favorites:

The 24 Hour Rule

Too often, we allow ourselves lag time in applying the knowledge we have acquired. We learn something and ‘let it sit’, only for the thought to lose it’s sharpness. As a result, its clarity erodes along with the sands of time.

A simple rule to counteract this: put a time cap on applying your new knowledge. Within 24 hours, require yourself to act on that information in some manner.

Create something. Teach something. Connect something. Again, how exactly you do so can vary. The goal is to constrain the time, not the medium. But whatever it is you choose to do, force yourself to do it quickly. The longer you wait, the less you will apply.

Implement a Consistent Review Process

A second favorite rule it so implement a consistent, replicable review system that forces you to revisit the information you have consumed.

Doing so ensures that you are not engaging in ‘drive-by-learning’, skimming and scanning as much as possible and eschewing any form of depth. The more you review, and the more regimented the time intervals on which you do so, the more solidified your knowledge will become.

To share what this looks like in practice, this is the logic that underpins two of the series I write - my Book Notes and What I Read This Week. Each operates around a hard and fast rule that forces me to re-engage with the content I have consumed, so that I may extract information from them and reinvest it back into my work. The two rules:

No new books started until a Book Notes article is written and published on the most recent one.

No new digital content consumed until I have published a ‘What I Read This Week’ article oriented around the information read the week prior.

These rules are designed for biases I’ve uncovered in my consumption habits - specifically a tendency to want to move onto the next piece of information without properly digesting the prior one.

Yours process likely will - and should - look different. But the more you mandate a review process, the more you will get in return.

Closing Thoughts

Some final thoughts to take us home.

By thinking of knowledge acquisition in a similar manner to financial dividends, we gain a more principled understanding of both how to acquire and apply our learnings.

The first step is to do the work to generate an intellectual profit. We can spend a great deal of time discussing what to do with our intellectual dividends, but the point is moot if we are not acquiring them in the first place. Just like financial dividends are a sign of a health company creating value, intellectual dividends are a sign of the health of your knowledge acquisition strategy. The higher the quality of the information you consume, the more you will get paid out.

Once you have acquired an insight, make sure you put it back to work. It is here where most of us fall short, withdrawing our profits on autopilot without any idea of where we might better leverage them. We consume and consume, never shifting from knowledge to wisdom via application. And in doing so, we watch the wave of compounding ride away without us on it.

The more we apply, the more we get in return. When we take our intellectual dividends and reinvest them - whether through building, teaching, or connecting - our knowledge solidifies, forming a foundation upon which we can build.

Yet while financial dividends serve as a useful analogy to help us contextualize the process of learning, the returns we earn from reinvesting in companies pale in comparison to the ones we earn from reinvesting in ourselves. When you consider that knowledge acquisition never stops, you recognize that intellectual payouts come at a frequency that their financial parallels never could. We shift from quarterly dividends to daily ones, earning a payout each time we choose to tap into the power of reapplication.

And the more frequent the payouts, the faster the compounding rate becomes. Intellectual dividends quickly come to far outstrip anything we could do with our financial ones.

So make the choice to move from passive to active, from intangible to tangible. Read, listen, learn. And most importantly, apply. Take your intellectual dividends and reinvest them back into yourself.

And watch as compounding brings you along for the ride.