1 hour. Evaporated into the ether as if it never existed. 60 minutes. 3600 seconds. 0 value. Talk about bad ROI.

I fall into this trap often. Sucked into endless rabbit holes. Trapped in the cheap dopamine cycle of Tweets and Tik-Toks, Reels and Stories. Washed away by the firehose of information.

And I know I’m not alone.

There is a battle going on today, a hidden one with powerful implications. One stemming from the informational vortex created by our digital world.

It is the fight for our attention, for our focus. For our ability to parse signal from noise.

For the past few years, I’ve been on the journey to regain control over my attention. Searching for strategies to fight back against the information waging war on my mind.

In the process, I’ve tried to carve out some lessons - my ‘philosophy of focus’, if you will. The following is an attempt to distill these insights into a practical roadmap. One that can help us take the power of focus back into our own hands.

Lets start by getting our bearings.

A Battle of Signal and Noise

Today's world is a paradox when placed in the context of human history. Where humans once lived in a world of scarcity, abundance is now the defining trait.

We no longer inhabit the realm of lions and bears. Instead, our modern age is one of bits and bytes Where information once took the form of cave drawings and scrolls, it now lives as electricity - words on a screen, transmitted at the speed of light. The medium has changed.

And as a result, so too has the magnitude. The printing press. The telegraph. The telephone. The internet. Each advancement in technology a new medium for broadcasting the secrets of the world. Each creating compounding effects on the amount of knowledge available in the world. Each amplifying the strain on our attention.

In the digital age, our options are abundant. Yet pitfalls accompany possibilities, and here we find no exception. As the magnitude of information grows, so too do the demands on our abilities to parse it. Content is compounding at a rate that far outstrips our cognitive capabilities, and a confounding problem has emerged as a result.

A story of signal versus noise.

There are a couple of underlying truths here.

First, more information does not equate to more truth. This is is easy to see. Simply watch how the internet turns one story into one hundred. Something happens, people write and report. The spins are all different, but the underlying kernel of truth remains unchanged.

Second, truth is constant. We neither add nor subtract it from the word, nor does it expand alongside the informational vortex in which we live today. Instead, we seek to uncover and bring to light that which already exists.

Put these two together, and the implications are clear: We are living in a world where noise compounds while signal stagnates, making more truth more difficult to uncover than ever.

A challenge arises, born out of a fundamental flaw in human biology: evolution has not shaped our brains to thrive amidst environments of high noise. In the saga of human history, information has been scare for much longer than it has been abundant. We are armed with primitive brains in and advanced world.

And the end result of biology adapted for scarcity in a world of abundance is simple - confusion. We know not where to look, what to pay attention to. The noise grows, a blinding blizzard of information through which we must trek to find signal.

The Illusion of Choice

A paradox is thus at play. The age of infinite information offers endless avenues for attention to pursue. Yet the majority are trap doors, masquerading as friendly bed and breakfasts. 'Come stay a while, and we will satisfy the desires of your heart', they say. Yet we find ourselves emptier upon departure than when we first arrived. They promise us signal, but all we get in return is more noise.

My experiences with cheap dopamine traps have revealed one of the worlds great illusions: while our choices appear infinite, they are in fact the opposite. If we are to get what we want out of our lives, there are only a finite number of roads that we can travel to do so. The set of choices we can make is a much smaller subset of the options afforded to us.

A story from Trevor Moawad, the late mental performance coach, highlights this dichotomy well.

In his book It Takes What it Takes, Moawad discusses the career evolution of Vince Carter. Known as a high flier early on, Carter began to shy away from highlight reel dunks as he aged. His rationale? Age and big dunks do not mix. The older he become, the more strain explosive plays placed on his body. Strain that compounded over the course of a game and the course of a season.

To Carter, each decision to take a lay up over a dunk was representative of the illusion of choice: the options we think we have are not options at all when placed within the context of our goals. Where others saw him making a choice on each breakaway, his choice was already made. He knew that every windmill dunk was a disservice to extending his career. The choice was already made.

Moawad sums up the less he took from Carter well, writing: “Do we have the luxury of choice if excellence is what we aspire to?

The Illusion of Choice helps put the fight for focus into context.

A world full of abundant possibility is also one filled with the illusion of abundant choice. Yet more options do not beget more choices. While the number of things competing for your attention grows, the set of choices consistent with your vision remains constant.

This is the Game of Attention in a nutshell.

The Game of Attention

We play the Game of Attention each day, from the moment we arise to when the lights shut off at night. Every step along the way a decision on where to place our focus. A choice.

In this game, choices determine the answer to the question ‘what am I paying attention to?’. And the response cannot be ‘everything’, else we risk averaging ourselves out to 0. A bi-product of the noise, we pursue everything - and in turn find nothing. We must recognize the illusion of choice at play so that we can take back control of our focus.

And so, let me propose the best antidote I have found, a counter-intuitive red-pill in a world in which we are encouraged at all points to ‘open our minds’: close yours instead. Make a contrarian bet to seal off your attention. Constrict your focus to play a game of filters so that you may re-exert control over the inputs influencing your attention.

The goal here is not to be ‘closed-minded’. Rather, it is to have strong opinions - values, perspectives, guidelines - that are weakly held. Convictions you are constantly squaring against information relevant to those convictions. To take a beginner’s mind to any piece of data that you allow into your mind rather than every piece outside of it.

Richard Feynman's '12 Favorite Problems' model has emerged as one of my favorite strategies for crafting these attention boundaries. A Nobel Prize wining physicist and renowned polymath, Feynman was once asked how he was able to live such a broadly impactful life. His response?:

“You have to keep a dozen of your favorite problems constantly present in your mind, although by and large they will lay in a dormant state. Every time you hear or read a new trick or a new result, test it against each of your twelve problems to see whether it helps. Every once in a while, there will be a hit, and people will say, “How did he do it? He must be a genius!

Feynman’s approach to creativity was thus to establish boundaries around his attention - his ‘dozen favorite problems’ - so that he could play with each of them infinitely and in unique ways.

Through this lens, a lesson about closed and open minds take shape. It is not an either or debate, but rather a question of ordering. Close your mind your first, so that you may more readily open it later. The path to focus, to identifying the signal in the world, first requires you to define the signal you wish to pursue so you know in which direction you need look. Identify the questions that pull at your soul, the ones you cannot help but feel the spark of curiosity to pursue, and let them guide you attention like beacons in the night. Find your favorite problems.

And as your focus illuminates new information along the way, open your mind to think like a scientist. Square it against your convictions to help crystalize your understanding of the problem at hand.

There is a catch here: to live the life you want - rather than the one the world wants for you - you must spend time thinking about what these filters look like for you. The questions that light a fire in your soul will be unique. As a full set, your 'twelve problems' cannot possibly be identical to someone else's. You are the only person capable of identifying what it is that draws the best out of you.

The questions we ask ourselves influence the ways in which we see the world - and the power to set these lies within your control. Choose your filters and the path to victory in the war of attention becomes clear.

Choose your filters, take back your life.

Filters at Play

Look around the world at those who have made sense of it, and you will see filtering at play under the surface.

Success leaves clues. And when considering high performers as a set, we find they share many commonalities when it comes to focus . While each of their ideas may be unique, the processes behind them are often more alike than we'd expect.

The closer you look, the more you'll notice the boundaries they place around their attention - guardrails that direct their focus and shape their perspectives.

Whether they recognize it or not, many rely on a singular 'big idea'. It is a lens - a filter - they apply to the world, allowing them to see opportunities hidden to others. To borrow from Charlie Munger, they 'find a simple idea and take it seriously.'

Some examples, to help contextualize this concept:

Elon Musk has built his companies around a singular question - How do I create a more abundant future for humanity? Tesla, Space X, and even his recent acquisition of Twitter are all downstream of this one big idea.

Jeff Bezos founded Amazon on the simple principle of improving the customer experience. 30 years later, this filter still directly influences the company’s operation.

Ray Croc - credited for the globalization of the McDonald's franchise - prioritized a simple, replicable menu. The resulting Dollar Menu became and American icon for years to come.

Howard Schultz centered Starbucks's first cafes around coffee only, prioritizing the quality of both product and experience. He waited nearly 30 years before adding any food items to the menu.

Jack Dorsey utilized constraint in designing the initial Twitter platform with a 140 character limit. It took the company 11 years to expand to 280 and beyond.

Notice that while each idea/product/company is different, there is a common thread: less, but better. Each founder made a deliberate choice to create a narrow beam of focus. Like a magnifying glass condensing light into heat, doing so allowed them to direct their full energy at a small subset of problems.

Thus, while filters appear to be about inputs, their true power lies in the domain of expression. The information you attune to will determine the actions you take, the things you build. Garbage in, garbage out, as the saying goes. If you want to express in a certain way, then being strategic about your inputs matters.

And so, recognize that the path to creative expression often begins by choosing to study a narrow band of ideas. Determine the subjects where your most powerful inclinations lie and monopolize the insights they provide.

Why Filters Work - Simple Wins

Why do filters work? Why have some of the world’s greatest minds employed them to resounding success? Because in complex environments, simple wins.

Abundant information introduces layers of complexity to our decision making processes. As the noise amplifies, so too must our efforts to parse it.

Amidst these conditions, simplicity serves as a superpower. It allows us to zoom out, to find the details with the highest value return, and to discard the rest. It helps us see the forrest amidst the trees.

Filters create clarity out of complexity by providing barriers through which we can pass information, distilling the noise into our own version of signal. Think of them like prisms - refractory devices that alter the shape of light. They have the power to bend, split, and reflect light - ie information - creating novel ways of expressing the initial inputs. Give two prisms the same narrow band of light, and you will find wildly different results.

Filters operate in an analogous fashion. In the same way that prisms alter the shape of light, filters alter the shape of information. They condense, distill, and reframe - all according to the uniqueness of their design.

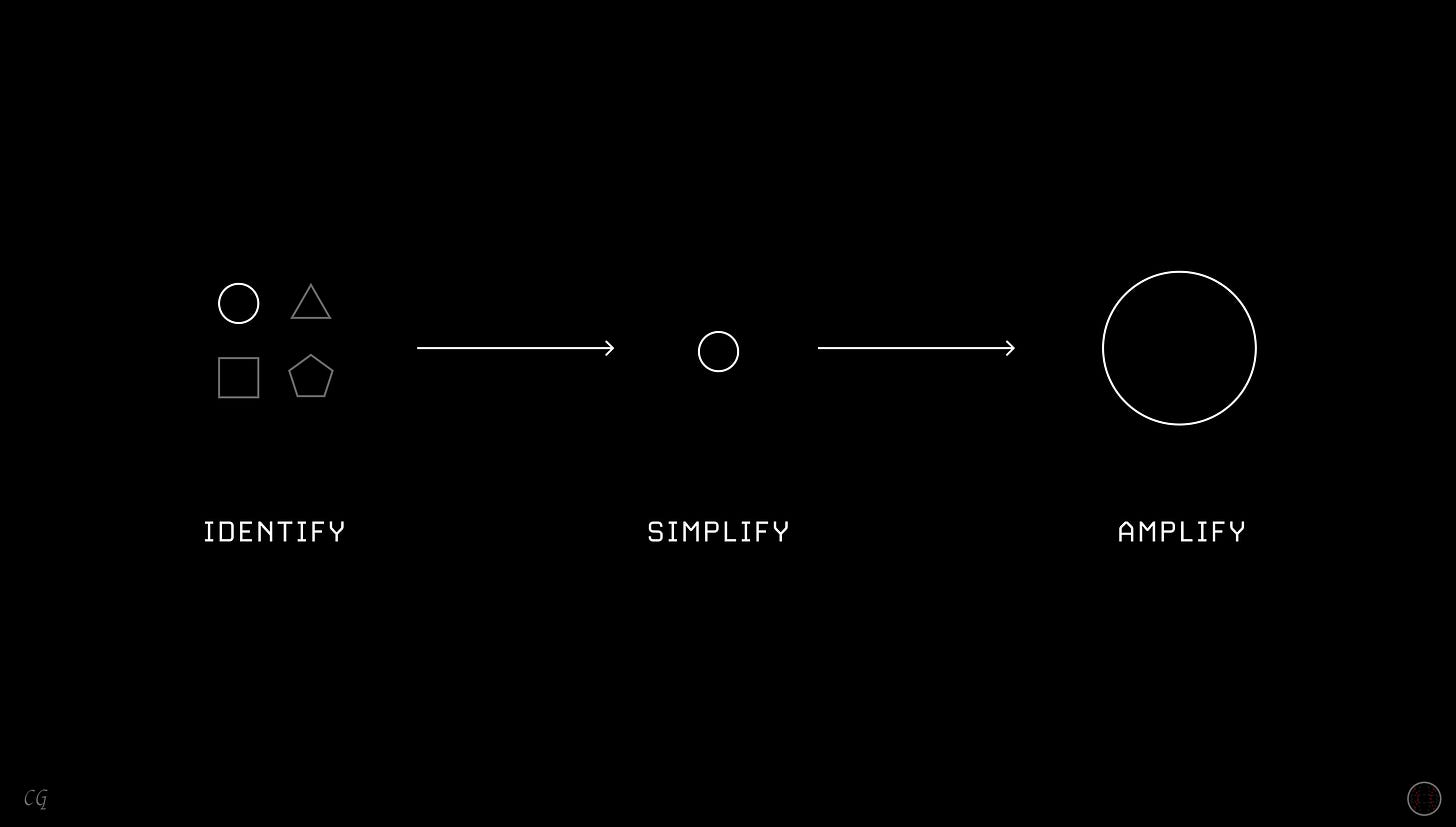

In his book The Creative Act, legendary music Rick Rubin provides a helpful triad to contextualize the art of filtering in relation to creativity:

“Source makes available. The Filter distills. The vessel receives.”

To Rubin, the world provides us with more source material - more information - than we can make sense of. As a result, we must learn to employ filters that reduce the information around us to what we deem most essential. By defining our filters up front, and cultivating them over time, we will be better able to find the signal we seek.

Filters are thus much more about reduction in quantity of information than reduction in quality. Think of them as boundaries rather than sieves - their role is to constrain the types of information you allow to capture your attention, rather than to make judgements about that information on the intake.

By reducing the magnitude of information allowed in, you in turn increase the purity. Less becomes more. Clarity emerges from complexity.

Final Thoughts - Insights from Practice

Some parting thoughts on parsing signal from noise and winning the fight for focus.

In a world where information is abundant and complexity abounds, our best hope lies in creating boundaries around our attention. By narrowing our peripherals in a manner aligned with our visions for the world, hope emerges - hope that we may reclaim control over a lost art: our ability to focus.

Filters are the mechanism through which to do so. They help narrow the infinite set of options to those aligned with our visions. And in doing so, they help us nourish voices that are distinctly ours. Rather than playing by the rules of others, we can begin to play by our own. Bringing more of our true selves to the world in the process.

As always, the best way to get better at the game is to play it. So as you practice the art of filtering over time, what once required effort will soon require little at all. The more you utilize your filters, the more finely tuned they will become.

But recognize that filters are not meant to be static. Rather, they should evolve over time, shifting alongside the sands of your interests. As your experiences expose you to the possibilities of the world, allow your filters to adapt accordingly.

Think of them like a flashlight - keep the beam of focus narrow, so that you may better avoid distraction. But do not be afraid to change the direction in which it points, illuminating new parts of the world so that you may better see amidst the dark.

And so, I’ll leave you with this: the path to focus is in your hands, if you wish to take hold of it. The battle of attention is won by constructing boundaries around your attention. In world of increasing noise, they are the path to drawing clarity from complexity.

Start by turning your focus inwards. Find the questions that pull at your soul, and allow them to direct your attention like a compass finding true north. Let everything else pass by.

Play by your own rules, win on your own terms.