The Theory Of Athletic Relativity

A treatise on 'athleticism' in the modern era of sports

Hey Everyone! 👋🏻

Happy Tuesday, and welcome back to another edition of The Gunn Show. Hope you all had a fantastic week since we last spoke.

We are back today after last week’s post on systems and the value of doing things that don’t scale, which you can find below in case you missed it and would like to give it a read:

For this week’s edition, I wanted to share some thoughts I had that stem from an article I came across in The Athletic on Friday. Titled ‘Patrick Mahomes and the Secrets of the Dad Bod: What We Get Wrong About Athleticism", the piece was a nuanced discussion on the topic of ‘athleticism’ through the lens of some of sports most prominent - yet unconventional - athletes. Citing all-world players from professional sports like Mahomes, Nikola Jokić, and Luka Doncic, among others, the author makes a compelling case that athleticism doesn’t always look like we expect it to; the ‘bigger, faster, stronger’ framework is too limited, and that an overt reliance on it can result in us missing what truly makes some of the world’s most spectacular athletes so special.

I think the piece is worth the read if you have some time today, and find myself largely agreeing with the premise that it puts forth. But with that said, I wanted to share some additional thoughts on the topic that stem from my experiences in professional sports.

Over the last 7+ years, I’ve been fortunate enough to be ‘in the arena’ when it comes to evaluating/developing world-class athletes - and as such, I think I’ve learned a thing or two along the way about what constitutes athleticism - as well as why we tend to get confused about it. Today’s newsletter is my attempt to crystallize some of those insights and share them with you all to further the discussion.

And so, without further ado, today’s roadmap for my perspective on athleticism:

Beginnings - The human need for explanations as a rationale for why we care about athleticism.

Proxies - Conversation on the evolution of our attempts to quantify athleticism over the years

Shortcomings - Where our traditional assumptions about athleticism fall short

The Theory of Athletic Relativity - An attempted redefinition of what constitutes true athleticism

Let’s get to it.

- CG

The Theory of Athletic Relativity

Beginnings

For starters, it’s worth asking two important questions as it relates to athleticism: where does it come from, and why do we care?

It goes without saying that we humans have an endless fascination with the concept of athleticism, so much so that you’d be hard-pressed to emerge on the other side of a sports-centric conversation without so much as having brushed the topic. From radio talk shows to TV back-and-forths, water cooler convos to draft room break downs, the amorphous ‘athleticism’ debate seems to permeate every corner of the sports discourse.

But why?

I believe our fixation on athleticism stems from a simple truth: we humans have an insatiable desire for explanations. As long as we have existed as a species, it has never been enough for us to simply observe something; we must also be able to say why it happened, to find a rationale for how that thing came to be. To find the cause behind the effect in order to close the loop and satisfy our fundamental need to make sense of why the world around us works the way it does.

And it is no different when it comes to sport. Certainly, we relish in the opportunities to see the what - feats of athletic skill acted out on the field of play. But we also must satisfy our needs for the why and the how so that we can find an underlying explanation for why certain athletes, and thus teams, are capable of things that others are not.

It is here where the well-intended yet frustratingly misleading terminology of ‘athleticism’ draws its roots as a subjective descriptor meant to help our brains understand what our eyes can see. By reducing feats of sports performance to a single catchall term, we in turn create a mental shortcut that helps us process and categorize the complex physical abilities we witness. A linguistic placeholder for something our minds struggle to fully comprehend - the remarkable capabilities of the human body in motion.

And in doing so, we find the explanations we seek for why sports - and thus athletes - are the way they are. At least that is our hope.

Because as we will see, the reality of athletic feat is far more complex than a single word can capture.

Proxies

While the history of the word athleticism carries with it a hallmark of subjectivity, that does not mean we haven’t been trying our damndest to put objective frameworks in place to better quantify what we mean by it.

Throughout the history of sport, we’ve long been on the hunt for ‘athleticism proxies’ - measurable tests that can be used as rough (although indirect) estimates for athletic ability. Things like the 40 yard dash in football as a proxy for speed, the vertical jump in basketball as a proxy for explosiveness, or bench press repetitions in power lifting as a proxy for strength.

What these proxies do is allow us to create a fundamental baseline for comparison, in the same way we put kids through standardized testing in education. By instituting a reliable testing standard for ‘athleticism’, we in turn define a common language that allows us to place various aspects of an athlete’s skill profile in context with those of his peers - across both time and space. A 100m sprint is the same in Europe as it is in the United States, a vert test the same in 1960 as it is in 2025. And in that standardization lies a powerful basis for assessing athletic skill.

The desire for athleticism proxies is so strong, in fact, that entire “Combines” exist in order to capture them. These combines have been long-standing staples for events like the NFL and NBA, systematic attempts meant to quantify athleticism through a pre-scripted set of tests in the hopes that the results can tell us some things about future performance. In fact, when it comes to the United States, Major League Baseball’s addition of a draft combine back in 2021 means that every major US professional sports league now holds its own version of a combine.

The rise of combines reflect our persistent desire to quantify and compare athletic ability through objective measurements. And yet, there is a problem: proxies are, by definition, approximations - meaning that while they may get close to describing the real thing they will never perfectly represent the things they aim to measure.

Take the NFL Combine. How representative are the tests actually of what makes for good football players? Perhaps not as much as we are led to believe…

As an example, consider a 2022 study from the University of Houston at Victoria which concluded that combine tests had limited impact overall on draft status. When comparing drafted players and non-drafted players, the researchers found that there was no significant differences across any of the six key physical tests (40 yard dash, bench press, broad jump, etc.). And while they did find that draft placement (ie where drafted players were taken) shared some correlation to broad jump and the 20 yard shuttle, the predictive power was limited overall. The same shortcomings even extend to the NFL’s longtime gold-standard cognitive test, the Wonderlic, which was removed from combine testing in 2022 after failing to show any significant value.

But this characterization may not be entirely fair to proxies. In fact it is worth asking a follow up question: is this actually what we care about when it comes to assessing athleticism? Predicting draft status? Or are we really trying to get at something much more important like how that player will ultimately perform down the road?

From this perspective, the data on proxies is somewhat more lenient - a 2020 study that looked at combine tests relative to future NFL performance did find some significant relationships indicators when looking across various positions. While not every test mattered for every position group, the researchers found that every offensive and defensive position did have at least 1 NFL Scouting Combine test that correlated with future performance, such as the 40 yard dash for wide receivers. So there is a bit of nuance here - more on that in a moment.

Regardless, we have enough case studies from football alone to know that proxies for athleticism are not always best followed with a blind eye. As stories like Tom Brady and Patrick Mahomes tell us, these tests don’t always tell the whole story.

And here we find another important question to consider: are these testing shortcomings merely a function of the specific proxies we’ve been using, or proxies as a concept themselves?

I think there is a compelling argument to suggest that the main issue lies not with our attempt in general to assess athleticism, but rather with how we have done so up to this point.

As we’ve tested and observed over the years in sports, calibration has been a necessity. No-one wants to rely on tests of athleticism that we know don’t work, a truth we see represented in the Wonderlic story. Athletic assessment is thus an iterative process - we keep what we think works, and discard the rest.

The result of this constant process of refinement is that our tests are getting closer to describing what athleticism actually looks like. Some of this is enabled by lessons from history, but a key driver here is the never ending arc of technological progress. As science enables new breakthroughs in assessment technology, we become better suited to assess down the athletic stack - in turn allowing us to better quantify the previously quantifiable.

There are numerous examples here, ranging from ball tracking technologies like Trackman and Rapsodo to force plates and even new-age cognitive assessment tools like S2. But one stands out above the rest: markerless motion capture.

With the advent of camera based systems motion tracking technologies like KinaTrax, we now have an unprecedented ability to assess - and thus describe - human athleticism within the frame of competition itself. And while much of the research on what exactly this looks like is being done behind the scenes in labs owned and operated by professional sports teams (no secrets from me today - sorry!), facilities like P3 (Peak Performance Project) are helping us get closer to the truth of what true athleticism looks like.

P3’s pre-NBA draft assessments of two uncharacteristic NBA superstars, Nikola Jokić and Luka Doncic - neither of which are renowned for their physiques - are instructive here. Consider the following story about P3 and Jokić from The Athletic’s recent article on the topic of athleticism, which gives us good idea of both where we are now - and where we are heading (for P3’s insights on Doncic, I’d encourage you to scrub through this page from their website):

In the last decade, as Jokić grew into an NBA MVP and one of the best basketball players in the world, the story of his trip to P3 and his 17-inch jump has become a part of his lore. In many ways, it’s actually the least interesting part of the story.

As Elliott’s team [at P3] evaluated Jokić, he was put through a series of tests. P3 tested his hip abduction, or how fast and far one can affect one’s hip when moving laterally. It measured second-order metrics like how quickly he could decelerate and how high he could jump two times in a row. And it looked at a list of what Elliott calls “granular biomechanics” — hundreds of variables that rate things like force production, loads and joint extension. When the tests were complete, P3 put the numbers into a machine-learning algorithm that clusters athletes into groups with similar attributes.

What was most revealing about Jokić was not the numbers themselves, but the players he compared to. He was right on the fringe of a group of guards that Elliot called “Swiss Army Knives” because of their ability to do anything on the court.

“They’re just like a B-minus to B-level in everything,” Elliott said. “And that’s Jokić. He may look herky-jerky to you. But looking at the data, we think it looks really beautiful.”

P3 gave the cluster a name: “The Kinematic Movers.” That cluster exists as a skeleton key to unlock how data and technology can unearth athletic genius and provide a fuller picture. A Kinematic Mover is not an explosive jumper. Nor particularly powerful. But grades out above average in almost everything, possessing a portfolio of some of the most useful physical tools and movements in basketball.

As a group, Kinematic Movers in the NBA have longer careers, on average, and accumulate more of the statistic Win Shares.

Pause to notice how far the term “Kinematic Movers” is from our traditional proxies of athleticism like the 40 yard dash, and you can’t help but get the sense that we are moving in the right direction. Clearly, our proxies for athleticism are getting better.

And yet, we still have a long way to go. Because, when it comes to proxies, an old adage about models applies:

All are wrong. Some are useful.

It is not enough to merely have proxies for athleticism in place - we must go a step further, asking ourselves what they truly tell us. And even more importantly, what they don’t.

But in the defense of proxies, I think there is something else to blame. Because proxies, after all, are only as good as the thing they are trying to define.

And so, the real boogeyman isn’t our tests for athleticism, nor our desire to define it. No, it’s something else entirely:

The mistaken illusion we have that athleticism can be defined as a singular thing alone.

Shortcomings

Consider the fact that there is no universal combine when it comes to sports, and you will see what this means.

While there may be similarities across different ones - such as the NBA and NFL both testing vertical jumps - each combine stands largely on its own, a distinct combination of athletic proxies meant to be relevant only to the specific sport at hand. NHL players do not take batting practice in front of scouts, nor do NFL players participate in 3 point shooting contests at the NFL combine. Different athletes undergo different tests - and for good reason.

Intuitively, we understand why: no two combines are alike because no two sports are alike. The demands of a tennis match vastly differ from those of a soccer game, and thus so too do the skills needed by the individual athletes that play them.

Said differently: elite performance in one area does not guarantee success in another. Take basketball players, for example, who are incredibly athletic when it comes to the sport-specific demands of basketball, but more often than not incredibly un-athletic when it comes to the skill of baseball. As evidence, I present to you the following montage of NBA players throwing out first pitches at MLB games:

It follows that athleticism is not a ‘one-size-fits-all’ concept - it is relative instead. To the sport within which we are trying to define it, and the individual feats of athletic skill that sport therefore requires.

An interesting extension of this insight it that it is true across sports, certainly, but also within them.

Consider the NFL, in which quarterbacks have very different positional demands - and thus skillsets - than running backs. To compare Tom Brady and Patrick Mahomes to the likes of Saquon Barkley and Derrick Henry on the basis of a singular definition of athleticism is a fool’s errand. Barkley and Henry far surpass the QBs in our traditional athletic proxies, but does that really tell us anything? All four are exceptional performers relative to their position groups - and in the end, that is what really matters.

My favorite example of this comes from close to home: the skill of hitting in baseball, when viewed across different position groups.

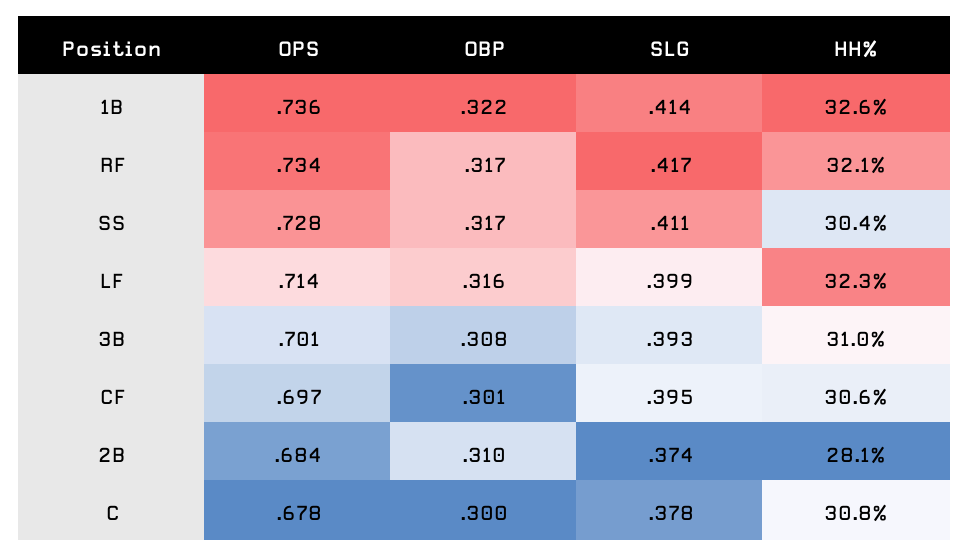

Take a look at the following chart, which details league average OPS, OBP, SLG, and Hard Hit rates for each position on the diamond:

Clearly, offensive ‘skill’ (or offensive athleticism) varies widely depending on the defensive position a player plays. Take the disparity between catchers and first baseman, for example: on average, backstops have a nearly 60 point lower OPS compared to their positional counterparts but 90 feet away. Does this mean that catchers are any less athletic when compared to first baseman? Of course not. All this tells us it that relative to the athletic skill of hitting as measured by the ‘proxy’ of OPS, first baseman tend to grade out a bit better.

Taking this example further, we can look at the breakdown by ‘part’ of the field - those that play in the middle of the diamond (ie catchers, second basemen, shortstops, and center fielders) versus those that play in the corners (first basemen, third basemen, left fielders, and right fielders):

The takeaway is clear: offensive skill tends to be a bit more prevalent in the corners of the field than it does up the middle. But again, these numbers don’t necessarily tell us which players are more ‘athletic’ than the others. Rather, the only reasonable conclusion is that different positions have different priorities. If you are going to play in a corner, you’d probably be best suited to have some athletic traits that map to offensive production. Conversely, up-the-middle players might be able to sacrifice some offensive athleticism as long as they supplement it in other ways.

And so again, we see the key truth about athleticism at play: it will always be relative to the demands of the sport-specific skill in which we are looking to assess it.

So why, when this is the case, would we be so naive as to think that we could ever find one catchall definition for athleticism?

If every sport - and every skill within it - has different requirements of its athletes, it stands to reason that athleticism must be viewed as a multi-dimensional concept rather than a singular trait.

And that requires an entirely different definition.

The Theory of Athletic Relativity

So to close, while I am skeptical about there being a singular definition of athleticism, I do think it is worthwhile to at least attempt to re-frame our pre-existing understanding of it by way of a more accommodating framework.

I’ll call it the Theory of Athletic Relativity, and we can define it as such:

The Theory of Athletic Relativity: Athleticism is only assessable according to the demands of the athletic task at hand.

The key underlying principle for this theory is that relativity is what makes athleticism unique, rather than a broad bucket of generalized proxies or tests. Because as we’ve seen, athleticism is only instructive so much as it informs us about an individual athlete's capacity to meet the specific physical demands of their chosen sports activity.

To truly assess athleticism accurately requires working backwards from the end: we must first ask ourselves what the athlete in question will be asked to do on the field of play. Only with this answer in hand can we orient ourselves in the proper direction and hone in on the specific athletic traits likely to lead to successful performance.

Too often, we operate in the reverse, defining amorphous athletic proxies that sound good in theory but have limited predicted power in practice. We then compound this initial mistake by letting these proxies lead us down the wrong path on the search of a universal definition of athletic ability, even when know that athletes come in all shapes and sizes.

In the modern era of sport, this fallacy of logic is particularly dangerous. As examples like P3’s assessments of Jokić and Doncic show us, we are getting increasingly better at quantifying - and thus assessing - the various components of the athletic stack. And yet while these advancements are undoubtedly positive when it comes to understanding how athletes operate, we still run the risk of making the same mistakes as we have for centuries if we are not properly mapping skills to demands. Because with increased precision comes increased confidence, regardless of whether we are focusing on the right things or not.

It follows that the best athletes might not be the best players, nor the best players the best athletes. At least when it comes to the traditional definition of athleticism.

So when it comes to athleticism, getting the right definition in place matters. We need one that allows for nuance and variability rather than one that forces us into overly simplistic categorizations, else we run the risk of misdiagnosing what makes the world’s athletes so special.

Athletic relativity is the necessary antidote, as it helps us avoid getting lost in an endless pursuit for universal athletic truths. Because in the end, athleticism isn’t about meeting some arbitrary standard - it’s about possessing the right combination of tools required to excel at the task at hand.

And that is something that is worth making sure we get right.